In a previous post, I reported that Coordinating Lead Author Overpeck wanted to “deal a mortal blow to the misuse of supposed warm period terms and myths in the literature”. The MWP was one such target; the Holocene Optimum was another. Overpeck said that there was “no need to go into details on any but the MWP, but good to mention the others in the same dismissive effort“, referring to the Holocene Thermal Maximum [Holocene Optimum] in the next sentence.

In today’a post, I’m going to discuss a July 31, 2006 (725. 1154353922.txt) email from IPCC Lead Author Olga Solomina who sent the following email to Overpeck expressing “more and more concern” about the IPCC statement that “the Early Holocene was cool in the tropics” – an assertion that was critical to Overpeck’s “mortal blow” project:

Hello everybody,

I attach here a version of glacier box and suggestions (in red) how to include there the reference to the new Thompson et al., 2006 paper.

In this relation – I am getting more and more concern about our statement that the Early Holocene was cool in the tropics – this paper shows that it was, actually, warm – ice core evidences+glaciers were smaller than now in the tropical Andes. The glaciers in the Southern Hemisphere (Porter, 2000, review paper) were also smaller than at least in the Neoglacial. We do not cite Porter’s paper for the reason that we actually do not know how to explain this – orbital reason does not work for the SH, but if we do cite it (which is fair) we have to say that during the Early to Mid Holocene glaciers were smaller than later in both Northen, and Southern Hemisphere, including the tropics, which would contradict to our statement in the Holocene chapter and the bullet. It is probably too late to rise these questions, but still just to draw your attention.

I am going to Kamchatka tomorrow, but will be avaliable by e-mail from time to time.

All the best,

olga

Nice to read of a climate scientist who isn’t going to Tahiti. Obviously, her interpretation of why the Porter review paper was not discussed in this context is disquieting.

The Solomina comment relates to the discussion of the Holocene Optimum in section 6.5.1.3 entitled: Was any part of the current interglacial period warmer than the late 20th century?

Overpeck and coauthors first acknowledged higher Holocene Optimum temperatures in mid-northern latitudes:

Climate reconstructions in the mid-northern latitudes exhibit a long-term decline in SST from the warmer early- to mid-Holocene to the cooler late-Holocene pre-industrial period (Johnsen et al., 2001; Marchal et al., 2002; Andersen et al., 2004; Kim et al., 2004), most likely in response to annual mean and summer orbital forcings at these latitudes. Near ice sheet remnants in northern Europe or western North America, peak warmth is locally delayed, probably as a result of the interplay between ice elevation, albedo, atmospheric and oceanic heat transport and orbital forcing (MacDonald et al., 2000; Kaufman et al., 2004). The warmest period in northern Europe and western north America occurs from 7 to 5 ka (Davis et al., 2003; Kaufman et al., 2004). During this mid-Holocene period, global pollen-based reconstructions (Prentice, 1998; Prentice et al., 2000) show a widespread northward expansion of northern temperate forest (Bigelow et al., 2003; Kaplan et al., 2003), as well as substantial glacier retreat (see Box 6.3).

Although the warmth in high northern latitudes is attributed to Milankowitch insolation variations, they also note early warm periods at high southern latitudes (New Zealand, South Africa, Antarctica), suggesting that “large-scale reorganisation of latitudinal heat transport may have been responsible”:

Other early warm periods are identified in the equatorial west Pacific (Stott et al 2004), China (He et al., 2004), New Zealand (Williams et al, 2004), south Africa (Holmgren et al, 2003) and Antarctica (Masson et al., 2000). At high southern latitudes, the early warm period cannot be explained by local summer insolation changes (see Box 6.1), suggesting that large-scale reorganisation of latitudinal heat transport may have been responsible.

Now the key point at issue: they asserted that the tropics behaved oppositely to the extratropics – warming since the Holocene Optimum:

In contrast, tropical temperature reconstructions, only available from marine records, show that tropical Atlantic, Pacific, Indian Ocean SSTs exhibit a progressive warming from the beginning of the current interglacial onwards (Rimbu et al., 2004; Stott et al., 2004), possibly a reflection of annual mean insolation change (Figure 6.5).

The above sentence is relied upon by Overpeck et al rely on in arguing against a global Holocene Optimum:

When considering the periods of largest temperature changes (Figure 6.9), paleoclimatic records of the Holocene provide no conclusive evidence for globally synchronous warm periods, especially because the temperature trends appear distinct in the low versus mid- and high-latitudes during the Holocene (Lorentz et al, 2006).

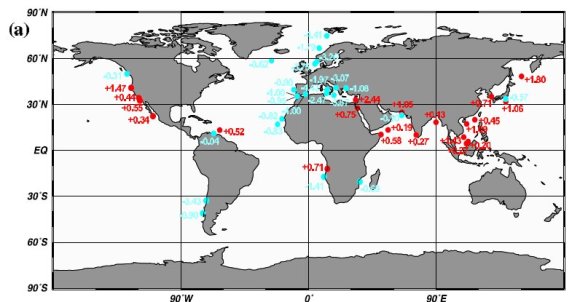

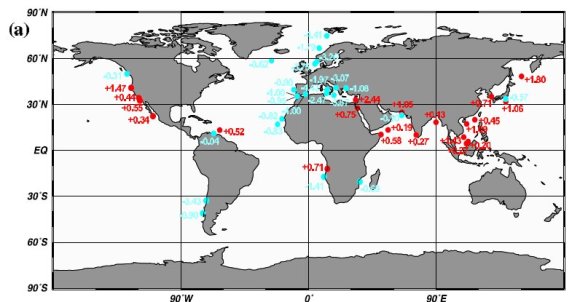

This idea was illustrated in IPCC Figure 6.9 – the blue rectangle denotes the “cool” tropics:

Overpeck replied to Solomina’s email as follows:

Hi Olga – it is not too late to ask these good questions. Glaciers can, of course, be affected by both temp and precip changes, so the question is really for Valerie (land) and Eystein (ocean) – are the land and ocean data from the tropics strong enough to outweigh what the glaciers are saying about tropical temps earlier in the Holocene? Lonnie’s Figure 8 (see attached) presents Hauscaran and Kilimanjaro data that suggest early to mid warmth in tropical South America and Africa that is (if the O-isotopes are temp) greater than today. Personally, I’m quite unsure that these are reliable temperature records, BUT if we want to make that case, we have to be convincing. What do terrestrial and ocean temp data say?

Thanks Olga for sending the proposed revised text – I think Eystein is putting finishing touches on the next draft for LA etc. review.

Masson-Delmotte chipped in as follows;

It seems to me that there is still a large uncertainty about the temperature versus precipitation effect on these tropical glaciers. Other indications from south America are related to lake levels with contrasted views in the low versus highlands.

Several references suggest that there is the end of a wet period after the early Holocene in tropical south America ; this is expected to induce an increase of 18O signals.

One review was conducted several years ago within the PEPI project (http://wwwpaztcn.wr.usgs.gov/pcaw/ and references herein).

I think that the state of the art is that we have no reliable proxy record that is sensivite to temperature only on the tropical lands for the Holocene; therefore the statement that was written for the Holocene was based on areas of the tropical oceans where SST reconstructions were published.

Do we have to write more explicitely about the uncertainty?

Valerie.

Jansen, who is an ocean sediment guy, concluded the discussion in the Climategate window, as follows:

Hi Olga,

I agree with Valerie that the ice core evidence is ambiguous. I would personally place more weight on the alkenone data, which is a reasonable well calibrated SST proxy. Foraminifer transfer function based SSTs and some Mg/Ca results that are available suggest a similar picture as far as I know. Of course it is possible and plausible that the tropical oceans are behaving in a non consistent manner and not all areas are showing the same signal, but a sizeable portion appear to do so in order to conclude as we do in the chapter in my opinion. Some signals may be due to changes in in trade wind induced coastal upwelling strength, but there are enough cores with alkenone data outside of these areas. If we were to say more about the uncertainties it may be the fact that proxies are seasonally skewed.

My conclusion is to let the chapter say what we say at the moment.

Cheers,

Eystein

I’ve bolded an important Jansen statement noting that some signals may be due to changes in “trade wind induced coastal upwelling strength”, but “there are enough cores with alkenone data outside of these areas.”

One reason why Jansen took care to distinguish upwelling zones is that upwelling zones in the 20th century appear to go opposite to the general trend of increasing SST. For example, an upwelling zone off Morocco has had exceptionally cold alkenone SST results in high-resolution data covering the 20th century -see CA discussion of Cape Ghir data here.

Interestingly, I had already wondered in Janurary 2007 about the potential impact of coastal upwelling sites on IPCC’s analysis of the Holocene Optimum and had assessed the sites in Lorenz et al 2006 against exactly this standard. See here .

In that post, I observed (long before Jansen’s comment became available through Climategate) that 5 of the 7 Lorenz et al tropical cores with a Holocene Optimum “cooler” than the present were from upwelling zones: three from the Arabian Sea, one from Cariaco (Venezuela) and one from Benguela.

Despite Jansen’s assertion that “there are enough cores with alkenone data outside [upwelling] areas”, there were only two tropical cores in Lorenz 2006 Figure 3 that purported to show a “cooler” Holocene Optimum (as against three that showed a warmer Holocene Optimum). And there are question marks against both of these cores – question marks not flagged in IPCC’s zeal to “deal a mortal blow” to the “myth” of the Holocene Optimum. Here is Lorenz et al Figure 3:

One Lorenz core (Core #12: GeoB5844-2) was from the northern Red Sea, where a major reorganization involving the Mediterranean dramatically changed salinities during the Holocene. Arz et al (Mediterranean Moisture Source for an Early-Holocene Humid Period in the Northern Red Sea) stated:

Paleosalinity and terrigenous sediment input changes reconstructed on two sediment cores from the northernmost Red Sea were used to infer hydrological changes at the southern margin of the Mediterranean climate zone during the Holocene. Between approximately 9.25 and 7.25 thousand years ago, about 3per-thousand reduced surface water salinities and enhanced fluvial sediment input suggest substantially higher rainfall and freshwater runoff, which thereafter decreased to modern values. The northern Red Sea humid interval is best explained by enhancement and southward extension of rainfall from Mediterranean sources, possibly involving strengthened early-Holocene Arctic Oscillation patterns and a regional monsoon-type circulation induced by increased land-sea temperature contrasts. We conclude that Afro-Asian monsoonal rains did not cross the subtropical desert zone during the early to mid-Holocene.

Changes in salinity can affect oxygen isotope; I am not familiar enough with alkenone data to comment on whether such dramatic changes in salinity would have any impact on the alkenone data. However, it’s something that one would like to see specifically excluded and commented on before placing too much reliance on the record. Aside from that, the northern Red Sea is hardly a type case for the world’s tropical oceans.

The other non-upwelling tropical core in Figure 3 is from the North China Sea (17940-2), where, once again, there was a major reorganization during the Holocene. Offshore southeast Asia has by far the greatest area of land that has been submerged during the Holocene – much submerged area today was dry in the LGM. This rearrangement also rearranged salinities and again one would want to see a specific exclusion and, if necessary, allowance for salinity in this area. Stott’s Mg-Ca temperature reconstruction in the Holocene for the nearby Pacific Warm Pool shows a warm Holocene Optimum. Needless to say, IPCC didn’t bother trying to reconcile the inconsistency. [Update: Reader tty in a comment draws attention to Leduc et al 2010, which attempts to reconcile Mg/Ca and alkenone results in a comprehensive survey. Leduc, G., Schneider, R., Kim, J.-H., Lohmann, G.(2010). Holocene and Eemian sea surface temperature trends as revealed by alkenone and Mg/Ca paleothermometry, Quaternary Science Reviews, 29(7-8), 989-1004. http://epic.awi.de/Publications/Led2010a.pdf%5D

Lorenz et al Figure 4 shows a larger population of sites than the 20 sites illustrated in Figure 3. However, the identity of the sites is not easy to determine on the present record. Lorenz et al stated:

All SST records were from ocean margin sites with sedimentation rates sufficiently high to provide SST records with at least one value per 1000 years. Detailed information on each SST record are given by Kim and Schneider [2004], including the original data references.

Kim and Schneider 2004 is: Kim, J.-H., and R. R. Schneider (2004), GHOST global database for alkenone-derived Holocene

sea-surface temperature records, http://www.pangaea.de/Projects/GHOST/, PANGAEA Network for Geol. and Environ. Data,

Bremerhaven, Germany. Unfortunately, this site is password-protected. I requested a password a couple of years ago, but received no acknowledgement and didn’t pursue the matter.

Lorenz et al 2006 Figure 4

Even without a full identification of all the cores, it can readily be seen that the core locations do not even approximately provide a random sample of the tropical Pacific, Indian – they are on continental shelfs. The sites in Figure 3 are illustrative in the sense that the sites with “cooler” alkenone Holocene Optimum are in the upwelling Arabian Sea, upwelling offshore Venezuela, upwelling Benguela, plus the Red Sea and the “Maritime Continent” shelf of southeast Asia. No samples from the open ocean.

Overpeck and associates didn’t report that glaciers in the Early Holocene were smaller than at present, as Solomina had proposed, choosing not to cite Thompson et al 2006 at all.

Update Apr 9, 2010: Leduc et al (2010) attempts to carry out the reconciliation between alkenone and Mg/Ca proxies ( a desideratum that I mentioned in my post of January 2007). It is an excellent article. It concludes:

The compilation of SST data available for the Holocene and derived from two different proxies (alkenone unsaturation vs. Mg/Ca ratios) suggests that the processes that drive the sedimentary record of the interglacial SST evolution may be unexpectedly complex and our understanding is only fragmentary. Although the alkenone-derived SST trends previously identified are robust, they are not reproduced by the Mg/Ca-derived SST records.

On the low-latitude warming indicated in the alkenone data (and relied upon by IPCC), they observe:

Why the global and persistent warming trend is recorded in almost all of the low-latitude alkenone records as such a strong Holocene SST feature (Figs. 1 and 3 a–c) is more puzzling, and can only be explained if alkenone-derived SST records are assumed to reflect the boreal winter season since it coincides with an insolation increase in the tropics. Therefore another factor may have had an impact at low latitudes, e.g., nutrient availability instead of light, since light is not a limiting factor for primary productivity at low latitudes. Possible is that in the permanently stratified tropical ocean where light is no limited low-nutrient surface waters are influenced seasonally by upwelling that acts synchronously to increase the surface water nutrient content – favouring primary productivity – and to decrease SST, potentially making coccolithophorids susceptible to blooms when SSTs are below the mean annual average. A feature that is in agreement with recent satellite observations for an inverse relationship at low latitudes between net primary productivity and temperature, the link between these processes being the upper ocean stratification (Behrenfeld et al., 2006).

Hand “Praised” McIntyre of Climate Audit

Lousie Gray of the DT reports

Stranger and stranger.

Unfortunately, Oxburgh “regrettably” “neglected” to mention this in his report.

Maybe this is a little more schizophrenic than it appeared at first blush. Like the NAS report.

Update: The New Scientist reports:

While I appreciate the compliment, I wonder what authority Hand has for his assertion that I claimed “Mann’s methods have “created” the hockey stick from data that does not contain it” – this is obviously untrue. The Mann data set obviously contains the hockey-stick shaped Graybill bristlecone pine data sets – I’ve talked at length about bristlecone pines as every CA reader knows. Had the Oxburgh Inquiry bothered to ask me, I would have been happy to clarify this point for them.

Hand says that the shape is more like “a field-hockey stick than an ice-hockey stick” – wonder how he knows that.