In an article in Nature today by Thompson, Kennedy, Wallace and Phil Jones claim:

Here we call attention to a previously overlooked discontinuity in the record at 1945,

Well, folks, the discontinuity may have been overlooked by Hadley Center, CRU, NOAA and NASA and by the stadiums of IPCC peer reviewers, but it wasn’t overlooked here at Climate Audit. The absurdity of Team bucket adjustments had been discussed in two early CA posts (here, here, here ). In March 2007, after publication of Kent et al 2007 showed the prevalence of buckets as late as 1970 (discussed here), I showed in a post entitled The Team and Pearl Harbour that this directly contradicted the Team’s Pearl Harbor adjustment and even showed the impact of a more plausible phasing in of bucket adjustments (see below). The issue was re-visited in Dec 2007 here.

In the Nature news discussion, Jones stated:

Climate scientists should think about data quality more often, says Jones, so that there is no opportunity for incorrect data to sow seeds of doubt in people’s minds about the reality of climate change.

Amen. Maybe instead of concealing his data – even to the extent of obstructing FOI requests for the identity of his station data, Jones should provide a complete archive of his data and methods, so that there can be some independent due diligence on his data.

Briefly reviewing my earlier post, in March 2007, I wrote the following:

One of the Team’s more adventurous assumptions in creating temperature histories is that there was an abrupt and universal change in SST measurement methods away from buckets to engine inlets in 1941, coinciding with the U.S. entry into World War II. As a result, Folland et al introduced an abrupt adjustment of 0.3 deg C to all SST measurements prior to 1941 (with the amount of the adjustment attenuated in the 19th century because of a hypothesized use of wooden rather than canvas buckets.) At the time, James Hansen characterized these various adjustments as “ad hoc” and of “dubious validity” although his caveats seem to have been forgotten and the Folland adjustments have pretty much swept the field. To my knowledge, no climate scientist actually bothered trying to determine whether there was documentary evidence of this abrupt and sudden change in measurement methods. The assumption was simply asserted enough times and it came into general use.

This hypothesis has always seemed ludicrous to me ever since I became aware of it. As a result, I was very interested in the empirical study of the distribution of measurement methods illustrated in my post yesterday, showing that about 90% of SST measurements in 1970 for which the measurement method was known were still taken by buckets, despite the assumption by the Team that all measurements after 1941 were taken by engine inlet.

I first examined the effect of a gradual changeover to engine inlet measurements using the 1970 distribution of Kent et al as a benchmark. A Climate Audit reader (Carl Smith) observed

it looks to me like the WWII records were dominated by engine-warmed intake data, perhaps because the chaos meant much of the bucket data did not get recorded, and after WWII it was business as usual with mostly bucket data resuming.

I illustrated this scenario, describing it as follows.

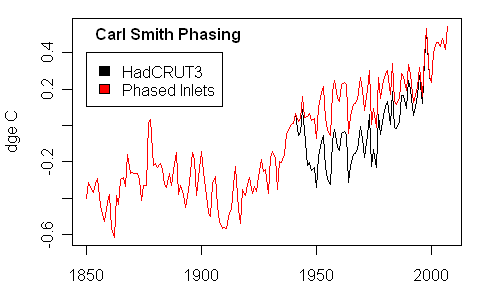

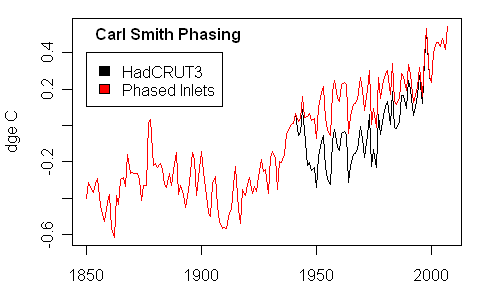

Let’s suppose that Carl Smith’s idea is what happened. I did the same calculation assuming that 75% of all measurements from 1942-1945 were done by engine inlets, falling back to business as usual 10% in 1946 where it remained until 1970 when we have a measurement point – 90% of measurements in 1970 were still being made by buckets as indicated by the information in Kent et al 2007- and that the 90% phased down to 0 in 2000 linearly. This results in the following graphic:

Black – HadCRU version as archived; red- with phased implementation of engine inlet adjustment

The transition from primarily bucket measurement in 1970 to primarily engine inlet in 2000 was supported by the following graphic in Kent et al 2007 discussed in last year’s posts e.g. here:

[UPDATE (May 30): A reader has contacted me to say that buckets in the 1970s were predominantly insulated buckets not uninsulated buckets and that the differential between insulated buckets and engine inlets is less than between uninsulated buckets and engine inlets (say 0.1 deg C, versus 0.25-0.3 deg C). So there may be a couple of things going on in bucket world – a change from buckets to engine inlets and a change from uninsulated buckets to insulated buckets. The latter possibility was not clearly articulated in Thompson et al, or for that matter in the predecessor articles, but may nonetheless be a real effect. IF such transition were complete by the 1970s, then this would contain adjustments in the 1980s to ones resulting from differences between insulated buckets and engine inlets, which would be less than between uninsulated buckets and engine inlets. I’ll take a look at this. I’m going to look for discussion of the transition from uninsulated buckets now said to have been in use after WW2 to insulated buckets. This episode definitely confirms my very first point on these bucket adjustments: whenever the adjustments are as as large the effect being measured, then there needs to be a replicable description and careful aassessment of all aspects of the adjustment process.]

Turning now to Nature’s news article describing this recent “discovery” by the Team:

The humble bucket turns out to be at the bottom of a perplexing anomaly in the climate records for the twentieth century.

A US–British team of climate scientists has now found a surprisingly simple explanation for the long-standing conundrum (page 646). It turns out that the mysterious drop is due to differences in the way that British and US ships’ crews measured the sea surface temperature (SST) in the 1940s.

Only a few SST measurements were made during wartime, and almost exclusively by US ships. Then, in the summer of 1945, British ships resumed measurements. But whereas US crews had measured the temperature of the intake water used for cooling the ships’ engines, British crews collected water in buckets from the sea for their measurements. When these uninsulated buckets were hauled from the ocean, the temperature probe would get a little colder as a result of the cooling effect of evaporation. US measurements, on the other hand, yielded slightly higher temperatures due to the warm engine-room environment.

The standard logbook entries made at the time contain no information about how the measurements were taken, so the cause was overlooked, says David Thompson, first author on the paper and an atmospheric scientist at the State University of Colorado in Boulder. As a result, the bias — which, although small, was large enough to produce the sharp drop in global mean temperature — was never adjusted for.

The article itself provides the following information on SST measurements:

The most notable change in the SST archive following December 1941 occurred in August 1945. Between January 1942 and August 1945, ~80% of the observations are from ships of US origin and ~5% are from ships of UK origin; between late 1945 and 1949 only ~30% of the observations are of US origin and about 50% are of UK origin. The change in country of origin in August 1945 is important for two reasons: first, in August 1945 US ships relied mainly on engine room intake measurements whereas UK ships used primarily uninsulated bucket measurements, and second, engine room intake measurements are generally biased warm relative to uninsulated bucket measurements.

In our estimate, we hypothesized a wartime changeover to about 75% engine inlet, with business as usual after the war, then gradually going to the 1970 distribution of Kent et al 2007. Thompson et al estimate 80% changeover to engine inlet during the war, with a return to business as usual after the war.

It’s nice to see that the Team has discovered what we at Climate Audit have known for some time – the assumption that all SST measurements switched over to engine inlets in December 1941 was absurd, ad hoc and introduced without any justification or textual analysis. It remained in climate literature despite obvious evidence that the majority of reported SST measurements in 1970 were being done by buckets.

In an accompanying comment, Forest and Reynolds say:

The SST adjustment around 1945 is likely to have far-reaching implications for modelling in this period.

My guess is that the aerosol stuff is going to be heavily affected. Aerosol histories always seemed to be designed a little conveniently to accommodate the supposed post-WW2 cooling.

It’s too bad that this foolish assumption has contaminated surface temperature histories and that IPCC was incapable of identifying an error known here at Climate Audit. As Jones said,

Climate scientists should think about data quality more often

Update: Would it have been possible for a Nature editor or reviewer to have located this prior Climate Audit discussion? If they had googled “climate world war 2 adjustments”, the very first item earlier today was http://www.climateaudit.org/?p=1276 . The present post has now superceded the earlier post and is now ranked atop Google on this search. But simply googling the expression would have identified a prior discussion of the issue.

Here’s an updated version of the graphic posted up last year using data downloaded today.

Update (June 1): Thompson et al stated:

The adjustments are unlikely to significantly affect estimates of century-long trends in global-mean temperatures, as the data before ~1940 and after the mid-1960s are not expected to require further corrections for changes from uninsulated bucket to engine room intake measurements. However, compensation for a different potential source of bias in SST data in the past decade— the transition from ship- to buoy-derived SSTs—might increase the century-long trends by raising recent SSTs as much as ~0.1 deg C, as buoy-derived SSTs are biased cool relative to ship measurements [10 – Worley et al 2005]

Whether or not this latter observation is correct, the citation, Worley et al 2005, provides no support for the assertion as the word “cool” is not used in it, nor do any occurrences of the word “buoy” contain supporting language.

Update Reference: Worley, S. J., S. D. Woodruff, R. W. Reynolds, S. J. Lubker, and N. Lott. 2005. ICOADS release 2.1 data and products. Int. J. Climatol 25, no. 7: 823–842. http://ftp.wmo.int/pages/prog/amp/mmop/documents/Jcomm-TR/J-TR-13-Marine-Climatology/REV1/joc1166.pdf